Feliciano Abaurre: Faces In Earth

Institute 193

215 North Limestone, Lexington, Kentucky 40507

11:00am - 6:00pm EDT

11:00am - 6:00pm EDT

On a hilltop just south of Dallas, Georgia, Feliciano Abaurre digs his clay. He lives there, surrounded by orchards, gardens, goats, sheep, pigs, chickens, rabbits, and an impeccably well managed vineyard of muscadines, the notoriously unruly grape native to the American Southeast. Beyond his talents behind the potters’ wheel, Abaurre, born in Mendoza, Argentina to a family of vineyard workers, also spins those grapes into delightful vintages of muscadine wine, a far cry from the insipidly sweet examples of such wines now common to roadside stands and gas stations across the rural South.

This combination of a skilled, technically rigorous traditional craft brought from a far-flung place and adjusted to the ecological realities of his home in the Georgia hills shares many commonalities with Abaurre’s approach to his ceramics. Initially, he learned the craft in Argentina, working as a production potter and learning various pre-columbian techniques from indigenous peoples in the area. When he moved to Georgia, he had to learn entirely new firing methods more appropriate to the hard red clay he could dig from his yard. Nearly all his materials come from the farm surrounding his home, or from neighbors and friends in the area. Pine needles and grape leaves make their way into the glazes in various forms, while a watertight finish might be achieved using beeswax from a friend’s hives.

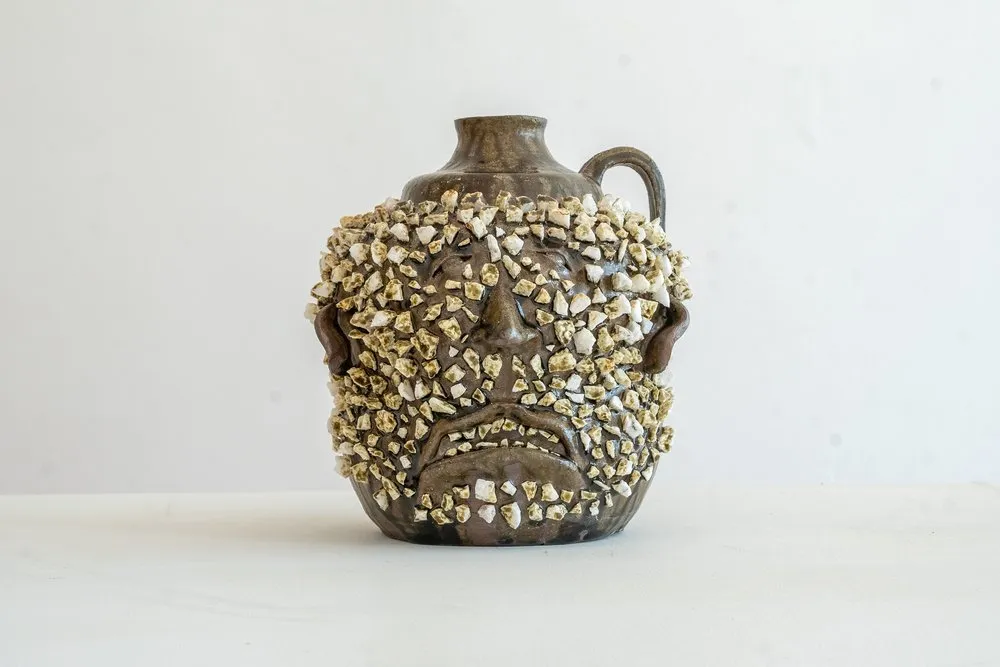

The pieces displayed here all maintain this link to the land and the natural world, while their visual elements radiate outwards into folk traditions from across the globe. One piece might craft the Georgia clay into the form of an indigenous American fertility goddess, with a finishing process pulled from 15th century Japan. Another might take a shape reminiscent of the face jugs made by enslaved Black potters along the Atlantic coast of the United States, but be glazed using a method Abaurre learned during his time in Patagonia. All maintain their presence as functional, useful objects for any household or farm, in addition to the beauty of their form and finish. These faces, all undeniably unique, speak to our reality as individuals shaped by history, yet capable of taking an active role in the universal unfolding of human cultures and experience, and in the relationship of that unfolding to the specificity of the places we find ourselves in – the plants that grow here, the rocks built up and worn down over eons, and all the faces that have passed through these landscapes before us.